Our Pair Programming Experience – or, the first time we nerded out together and learned a ton

Pair Programming – What is?

Pair programming is an agile software development technique in which two programmers work together at one workstation. One, the driver, writes code while the other, the observer or navigator, reviews each line of code as it is typed in. The two programmers switch roles frequently. (Wikipedia)

Why explain our experience?

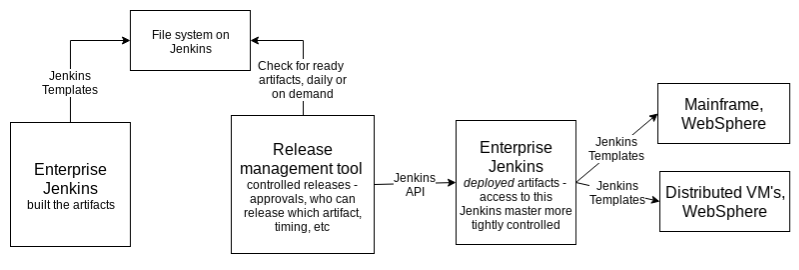

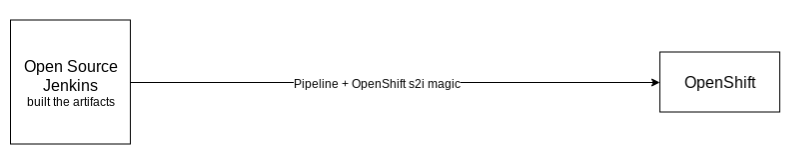

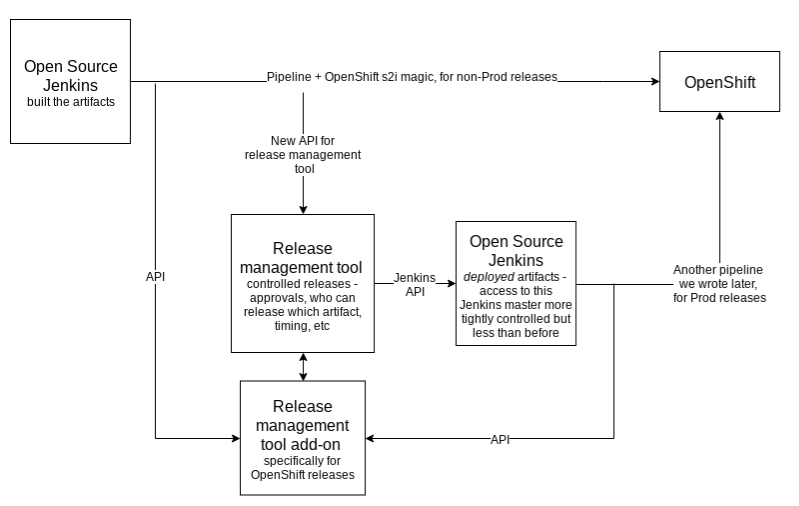

At the end of 2017, we were both OpenShift Architects at our last employer. We were working on integrating the new-to-us platform with the existing processes of the organization – especially the build, deployment, and release processes. Most of the applications on OpenShift would be Java applications, and all Java builds were done with Jenkins. There was a release management tool that was written in-house serving as a middle layer to control deployments and releases.

We (the organization) were also in the middle of transitioning from enterprise Jenkins + templates to open source Jenkins + pipelines. There were only a handful of people in the very large IT division who even knew how to write a pipeline – and we took on writing the pipelines (and shared libraries) that would prove out a default implementation of building and releasing to OpenShift. We knew this would be a huge challenge – if done properly, the entire company could run their OpenShift deploys on this pipeline, and it could be improved and grown as more people contributed to it via the internal open source culture that we were building.

We ended up doing this via pair programming – because we work really well together, mostly. However, because we’re both technology nerds and also people/culture nerds, and because pair programming has some push-back from more traditional organizations, we wrote down the benefits we saw.

I know some stuff, and you know some stuff, but basically we’re both noobs…

The team Laine was assigned to was the team that oversaw Jenkins administration and the build process, along with the in-house release management tool – but she’d only been on that team for about 4 months. She knew more about Jenkins than Josh, but….not by much.

Josh was the one who spearheaded bringing OpenShift into the company, and so he knew a lot of the theory of automating OpenShift deploys and had a rough idea of what the process as a whole should look like.

…basically, neither of us really knew how to do what we set out to do, and actually we didn’t intend to do something that fell into the realm of pair programming. We just already relied on each other for many things, including understanding and processing information, and we both deeply loved OpenShift and saw its potential for the company we also loved. We were determined to do as much as we possibly could to help it be successful.

What We Actually Did

Mostly our plan was to just…try stuff. We followed the definition of pair programming above some of the time – we took turns writing while the other focused more on review, catching problems, and planning the next steps. This was awesome, because we caught problems early just by keeping an eye on each other’s work – like, “uhh, you spelled ‘deploy’ D-E-P-L-Y, that’s not gonna’ work…”

Taking turns doing the actual coding also allowed us to churn through research while still doing development. We’re both top-down thinkers, which means that we understood the steps that needed to happen without knowing quite how we would implement each step. With one of us researching while the other was coding, as soon as one coding task was complete, we could more or less start right away on the next. Given the amount of research we had to do, this was huge in speeding us up. It also allowed us to switch up what we were each doing, and not get bogged down in either research or implementation.

In addition to taking turns coding vs overseeing, we also did a lot of what might be called parallel programming – we worked closely on different aspects of the same problem at the same time. This was also highly effective, but it required us to be very much on the same page about what we were doing. We did this mostly off-hours, via Slack communication, so…it wasn’t always a given that we actually were on the same page.

Despite the communication hijinks, or maybe because of them (it was really funny…), this was probably the most efficient of all of the coding work we did. If we got stuck or didn’t know how to solve a problem, the other could easily figure out how to help because we were already in the code. We also bounced questions and implementation ideas off of each other (efficiently, because we didn’t need to explain the entire project!), so…something like pair solution design.

And again, up there in overall efficiency, was some pair debugging. We could put our heads together to talk through what was broken (aside from typos…), figure out why it was broken, and land more quickly at the right solution to fix it. (See also: Rubber Duck Debugging)

Why it was Awesome

(Quotes in this section are from Strengthening the Case for Pair Programming.)

More Efficient

Two heads are better than one. Often, the part of development that takes the longest or is the most complicated isn’t writing the code – it’s figuring out what to do, and then figuring out what you did to break it and how to fix it.

Having a person there who understands the project as well as you do can speed up…well, literally all of that.

Higher Quality

…virtually all the surveyed professional programmers stated that they were more confident in their solutions when they pair programmed.

Pair programming provides better quality, hands down. We talked about this some already – a pair programmer can catch bugs before compiling or unit tests can, and they can catch bugs all the way from a typo to an architecture or design problem. Pair programming also requires by its very nature discussing all decisions – both design and implementation, at least at a high level.

…basically, you end up with an application where there’s been a design and code review for literally every aspect of the application.

Resilient Programming FTW (or, You Can Still Make Progress Even when Your Computer Dies)

We both had some laptop issues in all of this – Laine had some battery issues, and Josh had his laptop start a virus scan (slowing his computer to the point of being unusable) while he was trying to code. We got on Slack and helped the one who still had a working laptop, rather than that time just…being wasted.

Relationships, and Joy

…more than 90% stated that they enjoyed collaborative programming more than solo programming.

Laughing at mistakes, getting encouragement (or trolling) when we did dumb stuff, nerd emoji celebration when something went well – all of these were better because we were working together.

It was just…fun. There was joy in all of it, in both the successes and the failures. And there was joy in the shared purpose of setting something that we loved up for success.

When making a pair…

There are a few things we learned that were vital to pair programming going well for us. We think that the following pieces are the most important to a successful pairing:

Trust

Without trust, you lose some of the benefit of pointing out mistakes and instead spend the time you’d gain making sure that feelings aren’t hurt. Based on our experience, we actually think that this one is the most important key to success.

Temperament

You’ll want to find someone with approximately the same temperament and, uh…bossy-ness. We went with Bossy-ness Level: Maximum, but you do you. We both push for what we think is the right solution, and we kind of enjoy arguing with each other to figure out whose solution really is right. If either of us had paired with someone who was uncomfortable with conflict, chances are it…wouldn’t have gone well.

Technical Level/Skill/Experience

Pair programming probably isn’t going to work very well with a brand new associate paired up with someone who’s been in the industry for 10 years. That’s a lot of context to explain, so while this set up is amazing for training purposes, it isn’t the most effective for software delivery.

Lack of Knowledge

Look for someone who knows something you don’t about what you’re trying to accomplish. Laine knew Jenkins and is a Google savant, and Josh knew the OpenShift theory and reads constantly – when automating releases to OpenShift, it was a good combination.

And Finally

Pair programming provides a ton of value. It speeds up development, catches bugs sooner, and aids dramatically in design and implementation. It’s also fun, which is important and sometimes forgotten about in the just deliver more world of IT.

We loved working together on this, which led to much joy in learning the deep knowledge necessary to build a pipeline the whole company could use. And, even better, it worked – teams that joined OpenShift used and improved upon what we did, and those teams implemented continuous delivery on OpenShift. We’re both very sure that we never have been that successful if we hadn’t paired up on it.